Although startups hold great hopes for the future, they might possibly become the first victims of the current crisis. Similarly to other areas of the economy, they need government aid to survive; however, replacing market considerations with state bureaucracy should be avoided here as well. The methods introduced in Western Europe also point in this direction.

Startups are likely to be among the first victims of the coronavirus-induced economic crisis. Startups are extremely fast-growing young businesses developing innovative products or services and they have not yet entered the market with their products. They have little or no turnover and, in the absence of assets, cannot provide banks with ample collateral for borrowing. So far, their financing has been provided mainly from the capital of the founders and their family members and friends, whereas in the case of companies with the best growth prospects and promising great innovations, they have been financed from the investments of venture capitalists. For them, downtime is even more dangerous than for businesses that already have market revenues, as they often have little or no reserves at all, and they have not been able to prove yet whether the innovation they offer is truly viable. Venture capitalists, although they have the necessary resources from their fund investors, scrutinize their startups extremely thoroughly to prevent losses and decrease in returns. Only those companies whose products are seen as easily marketable in the changed post-crisis environment and whose survival does not require seemingly disproportionate sacrifices will be given another capital injection by them. Their phased investment contracts with provisions against risky investments allow them to do so from the very outset.

It is a question whether separate rescue packages are needed for startups in order to ensure that the knowledge, research results and technological achievements embodied in innovative startups, enhancing the competitiveness of individual countries, do not become null and void. Furthermore, if rescue packages are introduced, should they be developed at national and/or international level, and what set of tools are best suited to ensure that government assistance only helps startups that are able to adapt to post-crisis demand and it does not become a distortive intervention.

Behaviour of the venture capital industry in the crisis

When international capital flows stall at the beginning of a crisis, venture capital funds continue to have the capital they have been committed previously by their investors. In principle, these funds can still make “countercyclical” investments, though this is hampered by several things. Choosing the right investment targets is made difficult by the fact that company valuations have become uncertain. In the case of buyouts, the acquisition of the purchase price is also hindered by the narrowing of credit resources. In times of crisis, funds will only make investments from their own resources, i.e., without credit, if the owners of companies in difficulty are willing to set the value of their companies so low that it will bring a sufficiently high return to investors. Another problem is that the crisis has led to an increase in the share of assets held in venture capital funds in funded companies at the expense of free capital that can be mobilized for new investments. In the changed market situation, the funds will be unable to divest their equity in the planned period if the exit was scheduled for the time of the unforeseen crisis. Initial company valuations can no longer be validated in the new situation, thus sales must be delayed. Financing of companies that have been retained longer than planned can be a problem not only because it commits funds intended to other purposes, but also because the lack of exits makes it more difficult to raise resources for new funds as they usually use assets recovered from previous funds to finance their new commitments. In times of crisis, the resources of future investors will dwindle anyway, as the value of assets in public markets will also depreciate. The market power of companies selling their shares in exchange for capital as “sellers” and that of venture capital funds as “buyers” is changing in favour of the latter. Investors are reluctant to undertake relatively riskier investments at the expense of their impaired assets in an uncertain market situation, i.e., they prefer to “fly to safety”. As a result of the crisis, the fundraising of new venture capital funds will slow down, newly created funds will be smaller, and the number of fund managers will fall due to the shrinking market. Once the crisis is over, the number of exits will start to increase, and as a result, the resources of funds will be freed up and the capital will return to the investors. Fund investors will perceive an increase in confidence in the market and will be ready to make risky investments. That is, they will also be ready to finance new funds that are expected to yield higher returns than listed investments in return for the higher risk taken. The boom in fundraising and the opening up of the credit market will open the door to new venture capital investments, thus kicking off the boom in investments.

International experience

The measures taken until the beginning of April in the wake of the crisis caused by the coronavirus show that countries with developed capital markets, especially France and Germany, are trying to make it possible for startup companies to use the measures taken at national level to facilitate their survival. That is, governments first try to address the issue of liquidity, which can at the same time reduce the bankruptcy of startups. In addition, governments are earmarking public funds for venture capital funds in order to bridge the funding gap for startups due to missing private funds. However, when using public capital, market considerations are also taken into account, and in order to use government resources, it is necessary to involve a certain amount of private capital as well. Where private retail investors in venture capital funds have previously enjoyed a number of investment incentives, there are plans to increase these incentives.

The French government, which pays the most attention to startups in Europe, has announced a comprehensive EUR4bn refinancing and liquidity programme. The French state-owned bank Bpifrance has opened an EUR80m fund for venture capital investments in startups, to which private investors will have to contribute a similar amount. The German government has launched an EUR2bn support package to help startups affected by the coronavirus. The German government works together with venture capital fund managers to provide capital for German companies in difficulty due to the crisis. In addition, it allows even huge “fund of funds” from which private investors withdrew their capital to be replenished by public funds, such as KfW Capital or the European Investment Fund. A longer-term fund of EUR10bn has also been planned, which will be able to provide funding for larger startups. In the UK, however, no similar steps were yet taken in the first week of April, though startups and their supporting institutions strongly urged this in a joint proclamation called “Save Our Startups”.[1] The British Venture Capital Association (BVCA) would consider it appropriate to set up a GBP625m bridge financing fund organized by the British Business Bank to provide convertible credit from public capital up to GBP5m per company, supplemented by contributions from existing investors of the companies.[2]

In the meantime, measures have been taken at European level to support bank lending for small and medium-sized enterprises. An even more important EU initiative for startups was the so-called ESCALAR programme, announced in the first week of April, which allows EUR300m to be mobilized by venture and private equity funds financing both new startups and those in the growth phase. A special feature of this pilot initiative, which complements previous instruments to promote venture capital financing in the European Union and is expected to raise at least EUR1.2bn in capital, is that private investors will receive a larger portion of the returns than their public peers, that is, the EU funds.

Action plans in Hungary

Domestic economic protection measures include the following: measures to preserve jobs, investment subsidies to create jobs, support for priority sectors, financing companies with interest and guarantee subsidized loans, and family and pension protection measures. The scale of the measures is modest both in international comparison and in relation to the needs. Some of the measures are sector-specific. Unfortunately, no distinction is made between fully viable firms having only short-term problems due to the downtime as a result of social distancing and those where the economic downturn is also damaging in the medium term, thus it is questionable whether it is optimal to pour money into them. In fact, maintaining entrepreneurship would be the key to relaunching these businesses after the crisis is over, rather than simply restoring previous jobs. In the case of unilateral government selection, there is a great danger that not market considerations but subjective lobbying ones will prevail.

The announced government plans to help domestic companies do not specifically mention startups. Possibly, a 40% wage subsidy for those working in engineering and research and development jobs could help startups, as well as a 90% subsidy of tuition fees for IT training. However, the planned measures do not include proposals to make investments in venture capital funds more favourable to either business angels or institutions managing larger savings. At the same time, it is not necessarily disadvantageous that the most relevant proposal for startup companies, which calls for the establishment of a National Venture Capital Company and which was included in the package of economic crisis management proposals of the Budapest Chamber of Commerce and Industry (BKIK), has not yet been included in the rescue package.[3] The new capital fund included in the proposal would be set up as a specialized subsidiary of a so-called Nemzeti Válságkezelő Holding Zrt. (National Crisis Management Holding PLC). However, this venture capital fund acting as a public crisis manager would not focus on gazelle companies, it would specialize in financing acquisitions and mergers. The government, by investing public capital in viable companies that become undercapitalized as a result of the crisis, wants to ensure that the knowledge accumulated in companies that go bankrupt as a result of the crisis is not wasted. It is not clear how this public body would work together with bank or private co-financiers. It is highly questionable whether this organization would be able to perform the function assigned to it effectively if public fund managers decided to select companies to be rescued.

In addition to government aid, Hungarian fund managers, for example, GB & Partners, also started to help startup companies in trouble, offering HUF15bn to invest in 8-15 medium-sized companies with a turnover of HUF1-2bn. These are companies that have found themselves in a difficult situation due to the epidemic situation, however, in the long run they have a chance to grow and possibly expand internationally. This capital can be used for new investments, capacity expansion, acquisitions, mergers, international expansion, providing that the steps deemed necessary are supported by a well-thought-out financial plan.[4]

Capital supply of the domestic startup sector

In order to understand the current situation, it is important to know that the strong surge in startups was first experienced in Hungary between 2009 and 2010, i.e., in the years immediately following the global economic crisis. This was the time when startups were discovered as an innovative solution having special logic and methodology. An important feature of this period was the strengthening of the role of the state at European level in the financing of startups. It was also of great importance for startup companies in Hungary that the European Union launched the so-called Jeremie programme just at the beginning of the 2008 crisis. This programme was specifically aimed at improving the capital supply of early-stage companies through financial organizations that provided venture capital or preferential loans or provided guarantees. In the framework of this programme, the largest number of venture capital funds handling the largest amount of public and private funds was established in Hungary in the CEE region. However, only a very small proportion of these fund managers acted as real venture capitalists competently selecting the most promising companies and providing real help to the development and international expansion of an extremely large number of funded companies. The biased selection of fund managers and the lack of experienced fund managers led to a dilution of the fund management market as the main aim of the less technically savvy new fund managers was in many cases only to have access to public funds.[5] The direct presence of public venture capital funds creates competition to private investors, thereby impeding healthy market trends.

As a continuation of the Jeremie programme, the Hungarian government announced a number of new public capital development programmes for the next EU programming period, providing nearly HUF300bn venture capital for investments of startups and scaleups, also largely using EU funds. Thus, public venture capital is available in abundance to finance domestic companies in their early stages of development. Venture capital funds with market logic perceived signs of crisis in the competitive position of companies and they may review their portfolios based on their assessment of the expected new positions in the relevant sector. The fund managers can individually consider which of their firms needs immediate intervention, redesigning business plans, reviewing costs, or adapting sales plans to the changed situation. On this basis, they can decide to provide the additional resources they deem necessary, or, on the contrary, to cease their funding quickly in order to avoid losses. Improving their capital supply with public funds, just like in Germany, France and the UK, can be useful if the allocation of public resources is complemented by the involvement of private investors.

It is estimated that there are currently 150-200 startups operating in Hungary, and approximately 3-5 investments are made annually enabling significant international expansion (‘A round’). While there is ample capital available for the early-stage financing of startups, it is difficult to raise capital for the first major fundraising after the initial investment. In addition, the most important thing for truly globally minded startups that wish to grow on a market basis is not to raise fresh capital at all costs but rather to find investors with wide international relations and proper knowledge. However, there are only few of these on the Hungarian market.

In the decade before the crisis that erupted due to the coronavirus, a structural change took place in the Hungarian market of startups. An increasing number of startups in Hungary aim seriously to prepare for international expansion from the very beginning and are looking for partners who can help them entering foreign markets, and some of them simply skip domestic investors and immediately turn to reputable foreign investors. Others, planning international expansion from the outset, may utilize capital from local investors in the early stages of their development but using Hungary only as a test market. This also explains why domestic startups expect a large proportion of foreign investors in the funds to be included, although a significant amount of public venture capital funds is also available to companies in Hungary. However, in the case of many companies “international relations” continue to exist only as a slogan. In fact, Budapest has not become a startup hub drawing the attention of major international equity funds.

Thus, the crisis caused by the epidemic hit the Hungarian startup world in a situation where the crisis is also complicated by the fact that market conditions and behaviours in the domestic market of startups have not yet strengthened, and government participation is decisive even without the crisis. The key to success for companies living on public rent-seeking and government orders is not efficiency or value added, but rather maintaining proper connections with public decision-makers. The survival of the dominance of the government that previously catalysed the growth of this sector now hampers the development of the startup sector in Hungary as the natural selection of the market mechanism cannot prevail. Thus, a dual economy can be seen on the market of startups: some of them are trying to make a living from the market and stay away from public support, whereas others are trying to prosper through public assistance. As a result, the situation in the startup sector is not radically different than in other parts of the economy. It would be desirable if the government helped the startup sector with short-term survival tools during the crisis, similarly to other sectors of the Hungarian economy, without taking the task of market selection away from venture capitalists.

The article was prepared in the framework of project “K 128682” entitled “New tendencies in the development of business incubation institutions in Central and Eastern Europe,” implemented with the support of the National Research Development and Innovation Fund in the framework of the OTKA tender scheme.

[1] Woodman, A.: Startups call for help as UK support lags behind other offerings in Europe. 2020. 04. 06. (https://pitchbook.com/news/articles/startups-call-for-help-as-uk-support-lags-behind-europe); Stothard, M.: Save our Startups campaign warns that many of the 30,000 startups in the UK could collapse. 5 April 2020. (https://sifted.eu/articles/save-our-startups-covid19/)

[2] Wasteon, K.: BVCA urges Government to provide emergency bridge funding for early stage companies. 2020. 04. 07. (https://www.privateequitywire.co.uk/2020/04/07/284542/bvca-urges-government-provide-emergency-bridge-funding-early-stage-companies?utm_source=MailingList&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Private+Equity+Wire+09%2F04%2F20)

[3] BKIK: gyorsan, legalább ezer milliárdot kell mozgósítania a kormánynak (BKIK: the government needs to mobilize at least a thousand billion forints). Portfolio, 2020. 03. 30. (https://www.portfolio.hu/gazdasag/20200330/bkik-gyorsan-legalabb-ezer-milliardot-kell-mozgositania-a-kormanynak-422782)

[4] VG.HU (2020): Tizenötmilliárd forinttal segíti a kkv-kat a GB & Partners (GB & Partners helps SMEs with fifteen billion forints). vg.hu, 2020. 03. 29 (https://www.vg.hu/kkv/kkv-hirek/tizenotmilliard-forinttal-segiti-a-kkv-kat-a-gb-partners-2147277)

[5] Cf. Karsai, J.: Furcsa pár. Az állam szerepe a kockázatitőke-piacon Kelet-Európában. (A strange couple. The role of the state in the venture capital market in Eastern Europe.) Közgazdasági Szemle Alapítvány / MTA KRTKI KTI, Budapest, 2017.

Nem található esemény a közeljövőben.

A KRTK Közgazdaság-tudományi Intézet teljesítményéről A KRTK KTI a RePEc/IDEAS rangsorában, amely a világ közgazdaság-tudományi tanszékeit és intézeteit rangsorolja publikációs teljesítményük alapján, a legjobb ... Read More »

Tisztelt Kollégák! Tudományos kutatóként, intézeti vezetőként egész életünkben a kutatói szabadság és felelősség elve vezetett bennünket. Meggyőződésünk, hogy a tudomány csak akkor érhet el ... Read More »

Srí Lanka: a 2022-es gazdasági válság leckéje – A. Krueger Lessons from Sri Lanka Anne O. Krueger Jul 25, 2022 – Project Syndicate ... Read More »

A permanens válság korában élünk – J. Meadway We’re living in an age of permanent crisis – let’s stop planning for a ‘return ... Read More »

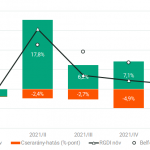

A 2021 végén, illetve 2022 elején tapaszalt 6, illetve 7%-os cserearányromlás brutális reáljövedelem-kivonást jelentett a magyar gazdaságból. A külső egyensúly alakulásával foglalkozó elemzések többnyire ... Read More »