On 9 December 2011 euro-area leaders once again gathered in an attempt to find a comprehensive solution for the euro-area sovereign debt and banking problems – but once again they failed to convince markets. Why is it so hard to overcome the current crisis? The answer is that the euro area has deep-rooted problems and for the most pressing ones no solution has been offered so far.

Let me raise ten important issues – the first four ones relate to pre-crisis developments, while the other six relate to issues highlighted by the crisis.

First, the rules-based Stability and Growth Pact failed, resulting in high public debt in Greece and Italy at the start of the crisis. Recent agreements, including the 9 December agreement, try to fix this problem with strong fiscal rules enshrined in national constitutions and an intergovernmental treaty with quasi-automatic sanctions. These institutions, if implemented, could help once the current crisis is solved, but are not sufficient to resolve current worries. For example, the situation could just be made worse if Italy had to pay a fine now.

Second, there was a sole focus on fiscal issues – and a consequent neglect of private-sector behaviour. This resulted in unsustainable credit and housing booms in countries such as Ireland and Spain, and the emergence of structural imbalances, such as high current-account deficits and eroded competitiveness. A new procedure, the so called ‘Excessive Imbalances Procedure’, was introduced with the aim of assessing private sector vulnerabilities and helping the countries to design remedies. Yet adjustment within the euro area could take a decade or so and hence quick improvements are not expected.

Third, there were no proper mechanisms to foster structural adjustment. Some countries, such as Germany, were able to adjust within the euro area on their own (ie Germany’s competitiveness improved considerably during the past 15 years), but others, such as Italy and Portugal, were not. The new ‘European Semester’, a yearly cycle of mutual assessment of fiscal and structural issues was introduced in 2010. This also aims to foster adjustment. This is useful, yet the jury is still out on its effectiveness.

Fourth, there was no crisis-resolution mechanism for euro-area countries and therefore the euro crisis came as a surprise without any clues about what to do about it. For troubled sovereigns some temporary arrangements were made: bilateral lending from euro-area partners to Greece and the setting up of two financing mechanisms, the EFSF (European Financial Stability Facility) and the EFSM (European Financial Stability Mechanism). The European Stability Mechanism (ESM), the permanent rescue fund with firepower of €500 billion, will likely be introduced in mid-2012. In the current circumstances having a euro-area rescue fund is a useful innovation, even though in other federations, such as the US, similar funds do not exist. However the firepower, even if augmented with IMF lending (the December summit committed to beef up IMF resources by €200 billion), is not really sufficient for big economies like Italy and Spain.

Fifth, the national bank resolution regimes and the large home bias in bank government bond holdings imply that there is a lethal correlation between banking and sovereign debt crises. When a government gets into trouble, so does the country’s banking system (eg Greece), and vice versa (eg Ireland). This problem could be best addressed with a banking federation, whereby bank resolution and deposit guarantee would be centralised, which would also require centralising regulation and supervision. A Eurobond, ie pooling sovereign bond issuances into a common bond for which participating countries would be jointly and severally liable, would help to break this lethal link. But Eurobonds would require a much stronger political union between member states.

Unfortunately, neither the banking federation nor the Eurobond is on the negotiating table.

Sixth, there is a strong interdependence between countries – much stronger than we envisioned during the good years before the crisis. The fall of a ”small” country can create contagion and the fall of a ”large” country lead to meltdown. Italy, for example, cannot be allowed to go bankrupt, because it would bankrupt the Italian banking system, which in turn would melt down the rest of the euro-area banking system through high-level interlinkages, and would also have disruptive effects outside the euro area. The best cure, again, would be the banking federation and the Eurobond.

Seventh, the strict no-monetary financing by the European Central Bank/Eurosystem means that euro-area governments borrow as if they were borrowing in a ”foreign” currency. This is because a central bank can in principle act as a lender of last resort for the sovereign, ie print money and buy government bonds (as the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England or the Bank of Japan did during the crisis). While the ECB has also started such a programme, it is extremely reluctant to do this and has said (so far) that these operations will remain limited. Lack of a lender of last resort for sovereigns is not a big problem when debt is low. For example, in the US the Federal Reserve does not buy the debt of the states of California, New York, etc, but buys only federal bonds. Even though California has been in deep financial trouble for the past three years, its eventual default would not have caused major disruption to the US banking system. The reasons are that the debt of the State of California is small, about 7 percent of California’s GDP (local governments in California have an additional 13 percent debt); moreover, this debt is not held by banks, but mainly by individuals. But Italy would be a game changer in Europe. The remedy to this problem is clear: setting up a stronger political and fiscal union which could provide the basis for changing the statutes of the ECB. In that case, the ECB need not purchase more government bonds; just signalling that it could purchase may help. But again, while there are pressures on the ECB to purchase more right now, there are no real discussions about what kind of political and fiscal integration should make such a role desirable.

Eighth, there is a downward spiral in adjusting countries, ie fiscal adjustment leading to a weaker economy, thereby lower public revenues and additional fiscal adjustment needs. It is extremely difficult to break this vicious circle in the absence of a stand-alone currency. In the US, the automatic stabilisers, such as unemployment insurance, are run by the federal government, which also invests more in distressed states – but in Europe we do not have instruments that could play similar roles and there are no discussions about them.

Ninth, there is a negative feedback loop between the crisis and growth not just in southern European adjusting countries, but in all euro-area countries. The funding strains in the banking sector, the increasing credit risks for banks due to weakening economic outlook, and the efforts to raise banks’ capital ratios may lead to a reduction in credit supply. But reduced credit availability would dampen economic growth further. Without effective solutions to deal with the crisis, growth is unlikely to resume.

Tenth, the current crisis is not just a sovereign debt and banking crisis, but a governance crisis as well. The response of European policymakers has been patchy, inadequate and belated, and they have thereby lost trust in their ability to resolve the crisis. Some observers have concluded that agreeing on a comprehensive solution is technically and politically beyond reach.

What are the scenarios in the absence of a truly comprehensive package? Until Italy and Spain can issue new bonds on the primary market, which they could do even after the 9 December summit, the current muddling-through strategy could continue. Italy and Spain’s current borrowing cost of 6-7 percent per year is high, but if these rates persist only for a limited period, they will not necessarily lead to an unsustainable fiscal position. The new governments of these countries could impress markets, leading to a gradual decline in interest rates. In the meantime the ECB can keep banks afloat. Yet even in this muddling-through strategy, a miracle is needed to revive economic growth, especially in southern Europe. But if markets were to decide against buying newly issued bonds from Italy and Spain, the pressure for a really comprehensive solution would be irresistible.

A version of this column is to appear in CESifo Forum 2011/4

Nem található esemény a közeljövőben.

A KRTK Közgazdaság-tudományi Intézet teljesítményéről A KRTK KTI a RePEc/IDEAS rangsorában, amely a világ közgazdaság-tudományi tanszékeit és intézeteit rangsorolja publikációs teljesítményük alapján, a legjobb ... Read More »

Tisztelt Kollégák! Tudományos kutatóként, intézeti vezetőként egész életünkben a kutatói szabadság és felelősség elve vezetett bennünket. Meggyőződésünk, hogy a tudomány csak akkor érhet el ... Read More »

Srí Lanka: a 2022-es gazdasági válság leckéje – A. Krueger Lessons from Sri Lanka Anne O. Krueger Jul 25, 2022 – Project Syndicate ... Read More »

A permanens válság korában élünk – J. Meadway We’re living in an age of permanent crisis – let’s stop planning for a ‘return ... Read More »

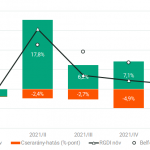

A 2021 végén, illetve 2022 elején tapaszalt 6, illetve 7%-os cserearányromlás brutális reáljövedelem-kivonást jelentett a magyar gazdaságból. A külső egyensúly alakulásával foglalkozó elemzések többnyire ... Read More »